The first digital deckbuilder was a Magic: The Gathering game from 1997 and it ruled

(Image credit: MicroProse)

My winning strategy in Magic: The Gathering relied on the Dingus Egg. Before I ever played the collectible card game with actual cards, I played a demo of MicroProse’s 1997 videogame version, which was just called Magic: The Gathering. That demo let you pick one of several single-color decks with tight themes and wacky names—the aquatic blue deck was called Ethyl Merman—and I favored a white deck called Eggscalibur. It relied on a simple combo: the Dingus Egg was an artifact that damaged each player for each of their land cards that got destroyed; the Armageddon spell destroyed every single land on the table. Since the combo affected both players, the trick was timing it so I had just enough life points to survive and my opponent didn’t. God bless the Dingus Egg.

That was my introduction to one of the joys of Magic: The Gathering, which is finding combinations of cards that do truly ridiculous things. (If the Eggscalibur deck had included Reverse Polarity, a white enchantment that turns damage caused by artifacts into healing, it could have been even more obnoxious.) The most infamous combos in Magic set up infinite loops or first-turn kills, but there are plenty of smaller, less game-breaking synergies that feel like one-two punches when you pull them off.

If MicroProse’s Magic: The Gathering had been nothing more than a fuller version of that duel mode for pitting decks against computer opponents it would have been fine. As it turned out, the final game was much more than that.

I’m gonna swing from the Shandalar

In 1987, MicroProse published Sid Meier’s Pirates! It was the first game with Meier’s name in the title, and was followed by Sid Meier’s Railroad Tycoon, Sid Meier’s Civilization, Sid Meier’s Colonization, and so on. Magic: The Gathering, the final game Meier worked on for MicroProse, didn’t have his name on it. Before its release, MicroProse played up his involvement, saying to Computer Games Strategy Plus that “Meier is programming a new, adventure game segment” and “He is also programming a stand-alone duel segment”.

Then Meier left MicroProse to found Firaxis and suddenly the company wasn’t so eager to advertise his efforts. Meier’s name was not only absent from the front of the box, but was removed from the credits entirely—still a common practice in the videogame industry when someone leaves a project before it’s finished, but absolutely a dick move.

(Image credit: MicroProse)

That “new, adventure game segment” was called Shandalar, and it ruled. In this mode you made your own wizard, choosing between often silly-looking faces and accessories, then walked across the plane of Shandalar dueling wizards and monsters via throwdown games of Magic. You can tell it’s old school Magic because it still has the ‘ante’ rule, which meant both you and your opponent put a random card from your decks on the line every time you played, with the winner keeping them.

That, and cards with archaic rules like ‘banding’, a keyword that let some creatures combine together in attack or defence, give Shandalar a definite flavor of 1990s Magic. It even had mana burn, a punishment for tapping too much land that costs you one life point for every point of unspent mana.

(Image credit: MicroProse)

There are towns where you can buy and sell cards and food as well as taking on quests in return for cards, gems that can be traded for cards, or manalinks, which increase your life total—rather than having the default 20 points of life, you start at 10 and work your way up.

While there’s no permadeath, and losing a bout simply means losing your ante, Shandalar has a surprising amount in common with modern deckbuilders like Slay the Spire, which it predates by 20 years. (Even Dominion, the first tabletop deckbuilder, wouldn’t come out until 11 years after Shandalar.) Playing Shandalar relies on that same balance between improvisation, finding synergies between whatever cards you find, and planning ahead, to figure out some OP combo and then plot how you’ll get there.

It’s not always great at teaching you how to play, though there is an amazing multimedia tutorial in which two actors wearing full wizard regalia explain the basics, with other actors appearing as the miniature knight, ogre, and elves they summon. The whole thing turns into a game show at one point. It’s cheesy, camp, and wonderful. (You may recognize a young Rhea Seehorn, aka Kim Wexler from Better Call Saul, as one of the teachers.)

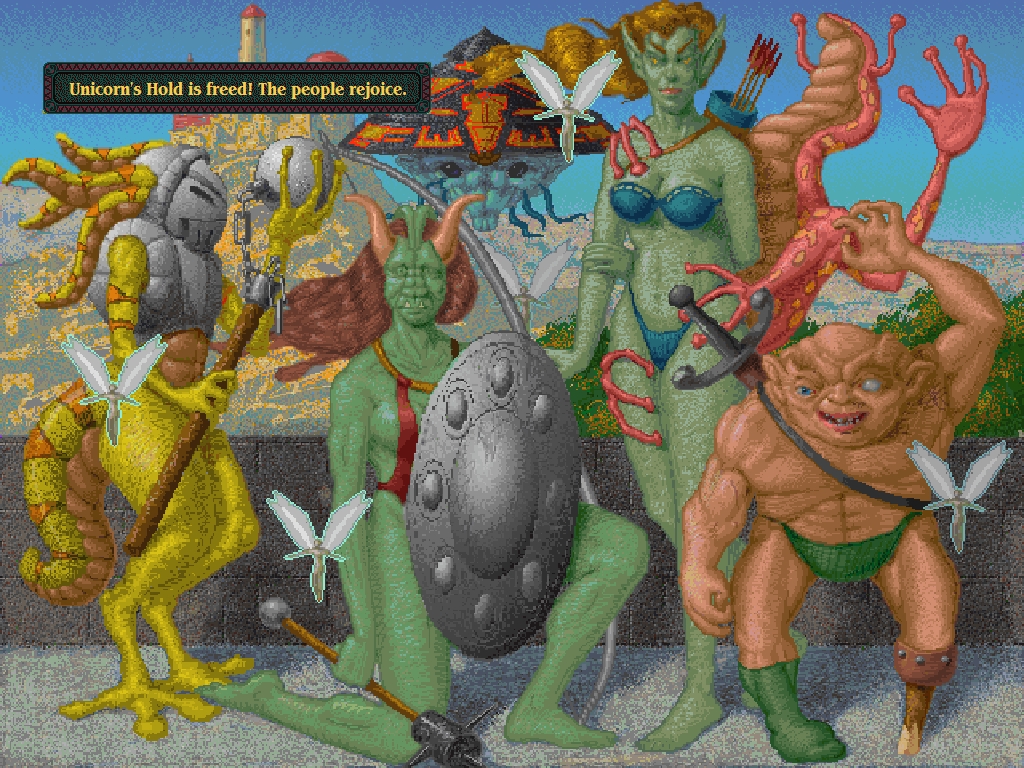

That sense of playful humor carried over into the game. The character creator included goofy options like a Groucho mask or just being a cat, one of the new ‘astral’ cards invented for the videogame was Goblin Polka Band, and after you saved a settlement that was under attack, the townsfolk who came out to rejoice were a pack of total goobers. One was a weird slimy thing hanging off an elf’s back, another was a floating blue jellyfish with a pyramid hat, and four identical fairies were clearly copy-pasted in to make things look even sillier.

(Image credit: MicroProse)The Mighty Nine

What was serious about Shandalar was the challenge. The best cards could only be found in dungeons, which had to be uncovered by foregoing the ante reward for defeating wizards and demanding dungeon clues instead. Each clue tells you a little more about what you’ll face, what color most of the enemies will be, and what rewards will be lying around. One dungeon might include a Black Lotus, a card that gives you three mana of any color. That’s good! The same dungeon might also have Power Struggle permanently in effect, meaning that every turn a random card swaps ownership. That’s bad!

Inside dungeons you can’t save, and your life points don’t refill between duels. It’s here, choosing between paths that might contain randomized rewards or riddles as well as enemies, that Shandalar feels most like Slay the Spire. Lose a single bout, or leave the dungeon for any reason, and the entire edifice vanishes. You have to go back to hunting for clues again.

(Image credit: MicroProse)

It’s worth it, because potential dungeon rewards include the Power Nine, cards from the early days of Magic that must have sounded like good ideas at the time but in play turned out to be game-bustingly overpowered. Cards like Time Walk, which lets you take another turn (something that might be fine in a regular board game, but is a killer in a one-on-one duel, and only cost two mana to boot). Or the Mox cards, each a zero-cost artifact that gives you a single mana of a certain color. Sure, it’s just one point of mana, but played early that extra point every turn puts you ahead of the curve for the entire game.

You needed these cards in Shandalar because of what came next. You had to fight the five guild lords of Shandalar, one per flavor of magic, and a final boss who could only be taken on after the Guild Lords were defeated: Arzakon, a planeswalker with hundreds of life points. On the hardest difficulty, he has 400. This is a game where you start with 10.

Against ordinary enemies a card like Lightning Bolt, which zaps for three damage, is quite useful. Against Arzakon having Lightning Bolts in your deck is a liability. To defeat him you have to construct the kind of heinous degenerate deck you’d never play against an actual human for fear of being exiled from polite society. To beat Arzakon you have to embrace the dark side, the kind of bullshit plays that make the Dingus Egg/Armageddon combo seem like child’s play.

(Image credit: MicroProse)

You might build an entire deck around nonsense like Black Vise, which damages your opponent every turn, one point for each card above four in their hand. You play as many as you can (thanks to Tome of Enlightenment, a magic item you can buy in town that increases the number of duplicates allowed), combined with all the Howling Mines you can carry—each if which increases card draw by one—and any other draw-forcing cards you can find. Ancestral Recall, Braingeyser, Timetwister, they all go in. Then you throw Ivory Tower on top, the reverse of Black Vise, which heals you for every card above four in your own inevitably bulging hand.

To ensure that deck’s efficiency you prune every land card except the two-mana kind, throw in Mox cards, and leave out all but one or two creatures. Instead, you rely on cheap board-clearing abominations like Wrath of God, which destroys all creatures including your own, and Swords to Plowshares, which returns summoned creatures to your opponent’s hand. Sure, it also heals them an amount equal to the creature’s power, but that’s trivial when you’ve got an illegal number of Black Vises going off every turn.

(Image credit: MicroProse)

That’s just one path to victory, even if it is the kind of victory that wouldn’t be possible in a tournament since it relies on cards that don’t exist any more. Other tactics include making a loop that generates infinite mana. Remember how Mox artifacts give you mana but don’t cost any to play? Hurkyll’s Recall bounces artifacts back to your hand so you can play them again, harvest the free mana, and repeat. Pop in some Timetwisters, which let you shuffle discarded cards back in the deck and draw a new hand so you’re guaranteed to redraw at least one Hurkyll’s Recall, and you’re good to go.

This combo was literally game-breaking, in that it would make the game crash. The positions of all those artifact cards were stored in memory every time you played them and would eventually become too much for the client to handle. The only way around it was to right-click and select Rearrange Cards each time to clear the slots from memory and prevent the crash.

Though Shandalar starts out with two actors in costumes teaching you the genteel art of magic, it ends by training you to become a loophole-exploiting rules lawyer of the worst kind, though in an environment where nobody gets hurt by it. It’s OK to play like a total prick when you’re up against someone with 400 life points and the fate of a whole plane is hanging in the balance.

This Magic moment

MicroProse released an expansion called Spells of the Ancients later in 1997 with more cards and a sealed deck generator, and then in 1998 combined both game and expansion in a package called Duels of the Planeswalkers, with even more cards and online multiplayer for duel mode. A final Gold Edition was announced at E3 in 1999, but never released. MicroProse didn’t last much longer, some of its studios shut down by owners Hasbro Interactive, and the rest by Infogrames, who took over in 2001.

(Image credit: MicroProse)

You can’t buy Shandalar any more. It’s available on the Internet Archive though, both the demo and a fan reimplementation of the full game from 2010, with support for 64-bit versions of Windows that otherwise struggle to run it. Other fan versions exist, though they add more recent cards to the decks and alter the visuals, losing some of that vaporwave aesthetic you get from backdrops with classical statuary and pastel blue crystal balls.

Though modern deckbuilders scratch a similar itch, there’s still nothing else quite like Shandalar. I’d love to see a remake or a similar singleplayer mode in Magic: The Gathering Arena, because sometimes I don’t want to play fair decks against real people. Sometimes I want to be a squatting polka goblin ruining a computer opponent’s day with the worst deck of cards that has ever existed.