Total War: Warhammer 3 review

What is it? Big fantasy armies racing to reach an imprisoned god.

Expect to pay $60/£50

Release date February 17

Developer: Creative Assembly

Publisher: Sega

Reviewed on: GTX 1080 Ti, Intel i7-8086K, 16GB RAM

Multiplayer? Yes

Link: Official site

It would have been very hard to predict the trajectory Total War has taken. It’s grown from feudal Japanese battles and a simple board game-style campaign to this, Warhammer 3, where armies can hop between realities, where daemons and ogres clash, and where troops are led by flying monstrosities—including one that’s as customisable as an RPG protagonist.

Creative Assembly has crammed plenty of surprises and oddities into this final act, clearly saving up its strangest experiments for the cataclysmic confrontation between mortals and Chaos. It goes in some strange directions, but always goes big, fully committing to Warhammer’s wonderfully over-the-top brand of fantasy.

The impetus for the conflict is a bearnapping. Ursun, Kislev’s hairiest deity, has been imprisoned by the daemon Be’lakor. To make matters worse for the furball, he’s also been shot with a cursed bullet by a corrupted Kislev prince. His roars of anguish open up rifts between realities, letting armies cross over to the Realm of Chaos, where they can fight to reach Ursun—some to free him, some to request a boon and others to steal his power.

Hellbound

It’s a setup that leads to a very different style of Total War campaign, where conquering the map is still encouraged but isn’t quite as important as reaching Ursun’s prison. Every 30 or so turns, rifts open up all over the map, spewing out daemonic armies and inviting mortals to enter Total War’s weirdest locations, culminating in massive survival battles against a daemon prince. The reward? The prince’s soul. Collect four and you can unlock the way to the big bear.

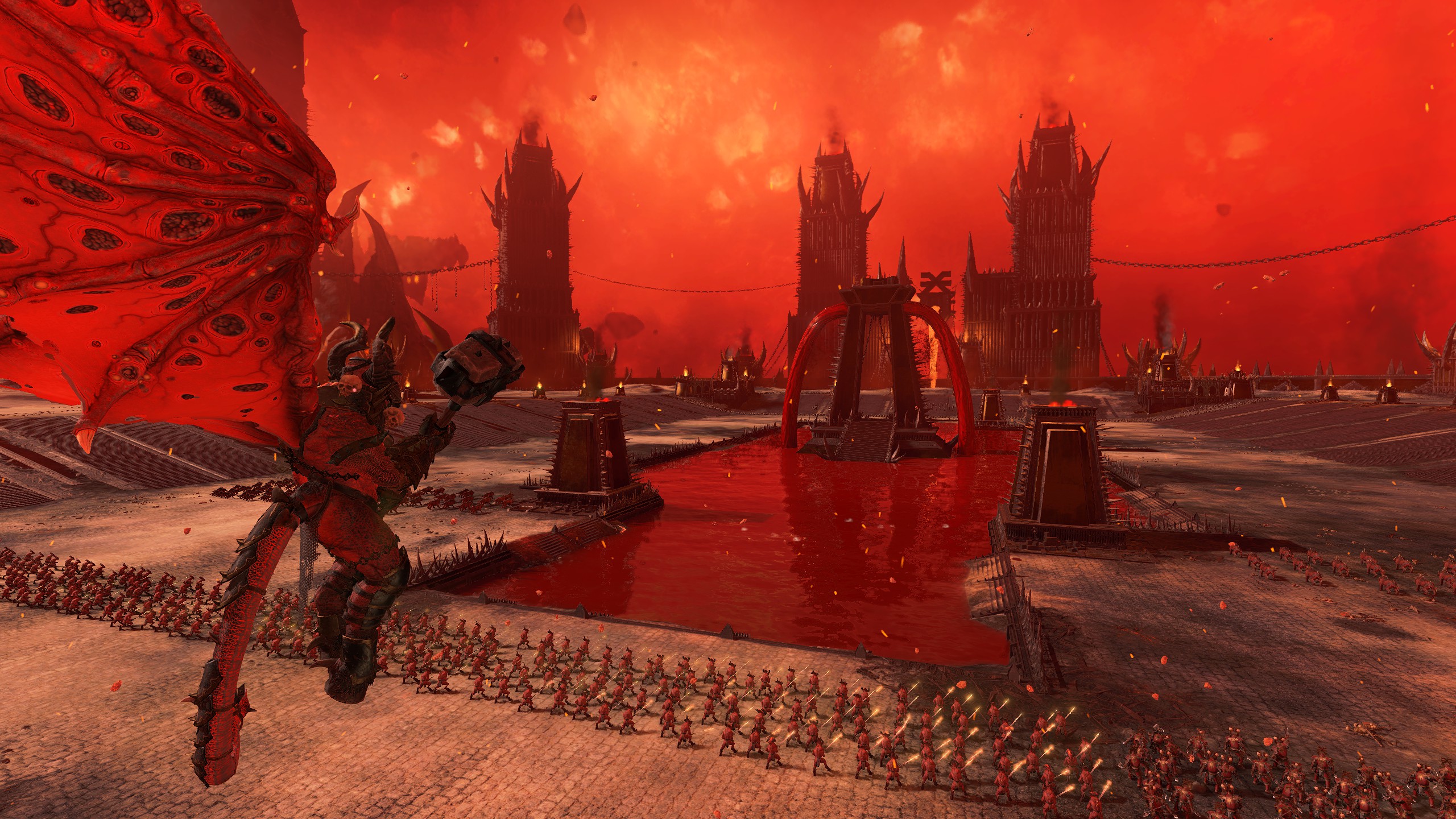

(Image credit: Sega)

Each section of the Realm of Chaos reflects the personality of its patron god. Nurgle’s realm is a pestilent, toxic nightmare where armies suffer constant attrition. Slaanesh’s ream is a purple-tinged series of rings connected by portals, and every time you walk through one the dark deity will try to seduce you with incredible gifts—but only if you leave without your prize. Tzeentch’s realm is a maze of floating islands connected by magic, where the route to the final battle is randomised. Khorne’s realm is the most straightforward: a hellscape where you simply beat up a lot of daemons and rogue armies until you’ve earned enough bloody glory.

You’ll likely spend around 10 turns in each, but they loom over the whole campaign. You know you’re going to need to be ready to jump into the next one, so you need to prepare by rapidly expanding and building the toughest army that you can. But since your best army is going to be in a different reality once the rifts open, you need to make sure your territory is still protected from daemonic invasions and mortal enemies.

Things can get extremely hairy, especially when the finish line is in sight. If it looks like another faction is going to get their fourth soul before you, you’ll need to act quickly, wiping them out before they get it. If that plan fails, though, you’ve still got a chance to claw back victory from the jaws of defeat. You need to immediately drop what you’re doing and wait for them outside Ursun’s prison. Defeat the army, and then you’ll have another 15 turns to catch up.

(Image credit: Sega)

That was one of my biggest concerns before the review: how do you win if you’re behind? Beat up your opponents is a nice, straightforward answer, and very Total War. But doing this also creates new wrinkles. In my first campaign, I was good friends with Nurgle’s faction. I loved those stinky boys. But when we both entered Slaanesh’s realm, and it looked like Nurgle’s lot were going to beat me to the final battle, I had to make a difficult decision. This wasn’t the last soul either of us needed, so I could have let my pal win this round, but did I really treasure our friendship that much? It turns out I did not. I got the soul, but the war against Nurgle lasted for a long time.

It’s by far the most unusual and involved campaign Creative Assembly has ever designed, and all this novelty made my first playthrough a treat. It has diminishing returns, however, and now that I’m more familiar with the Realm of Chaos, privy to its nasty bag of tricks, I sometimes resent dragging myself back there when I could be gobbling up settlements and wiping out other factions, putting it at odds with the sandbox.

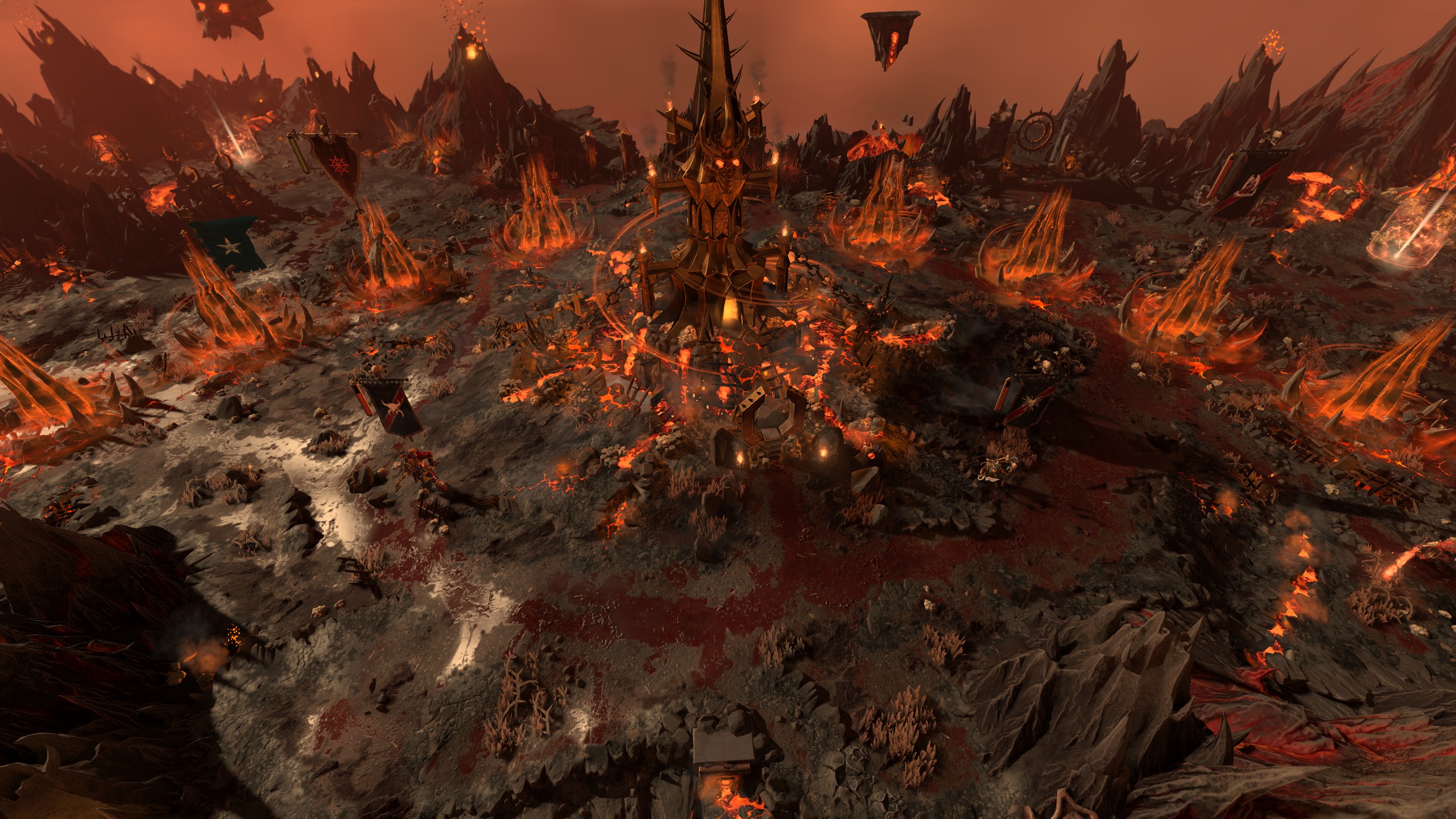

The same goes for the survival battle at the end of each of them. The wave-based assaults and tower defence elements, which let you spend resources earned in battle on various walls and towers—as well as reinforcements—give these battles such a different feel that I immediately found them compelling, but by my second campaign I started to see past the novelty.

(Image credit: Sega)

(Image credit: Sega)

Three multiplayer campaigns are available. There’s the multiplayer version of the Realm of Chaos campaign, and then historical campaigns set in Cathay and Kislev. The first two are for up to eight players, while the Kislev campaign is for three.

To keep these campaigns from getting bogged down, turn-time limits can be enabled, as can simultaneous turns. There’s simultaneous movement for armies now, too, so the pace is brisk.

In multiplayer battles, there’s a brand new mode that borrows elements from survival battles—which are singleplayer-only—letting you and your opponents fight over objectives to score points. There aren’t any fortifications, but you can bring in reinforcements.

Sure, the vast scale of them continues to impress me—they throw weaker troops at you but in greater numbers to create the series’ largest battles—but the tower defence elements are a bit on the thin side. You get access to four types of towers and walls, and a few specific locations where you’re allowed to build them. Think they’d be more effective elsewhere? Tough. And even with Creative Assembly trying to create lanes, everything is just too big, too wide, and you never get that sense that you’re manipulating the battlefield like you do in dedicated tower defence affairs.

While the survival battles start to lose their lustre after a campaign or two, new modes are very welcome, and the experiment does have a pay-off. Siege battles and the returning minor settlement fights also get these fortifications. These maps typically have a much more elaborate layout than the straight line of survival battles, with bridges and underpasses, plenty of elevation, and loads of places to create chokepoints. There are more ways for them to play out, and while you’re still limited to building on predetermined spots, the more dynamic nature of these fights means that the choice of where and what to build next feels tactical rather than arbitrary.

If you find that the survival battles aren’t to your taste, or if you’d rather skip them in later campaigns, you’re in luck. You can auto-resolve them like regular fights, and with generous odds to boot. Surprisingly, without the pressure to fight them myself, I actually find that I’m more open to taking control. It’s good enough to know that, if I don’t feel like it, I can leave it up to fate.

Wild Bunch

The bulk of the campaign still takes place on the more conventional sandbox map, some parts of which you’ll recognise from the first game—but thanks to Warhammer 3’s unusual factions, overfamiliarity shouldn’t be a problem. The highlight is the Daemons of Chaos faction. Each of the Chaos gods have their own crews, but the Daemons of Chaos, led by the aforementioned corrupted Kislev prince—now a daemon prince—is a united front, letting you recruit units from the entire pantheon and use each army’s unique abilities. The prince’s new form is malleable, letting you replace his limbs with new ones earned by dedicating your achievements to specific gods, or to all Chaos.

(Image credit: Sega)

The prince is also the subject of Warhammer 3’s excellent prologue—the best tutorial Creative Assembly has put together—and has the most personal connection to the campaign. Between the narrative structure and the astonishing variety of limbs and weapons you can equip him with, playing the Daemons of Chaos is almost like playing a Total War RPG. The story of a heroic knight becoming his land’s worst nightmare is also extremely evocative of Arthas’s fall in Warcraft 3, a story that’s still one of my favourites, so it had a rapt audience. It’s the most I’ve enjoyed a single Total War campaign.

With the Daemons of Chaos boasting all this flexibility and the most elaborate Legendary Lord, it does slightly dilute the impact of all the other daemonic factions. But they still have unique characters, starting locations and objectives that make them distinct enough to be worth taking for a spin. And while they all serve Chaos, they do so in very different ways, from Khorne’s bloodthirsty, take-no-prisoners approach, to Slaanesh’s sneaky, seductive ways.

Over time, the presence of these factions, along with the daemonic incursions from the Realm of Chaos, warps the mortal world. Chaos corruption exists in the other games, too, but there’s a lot more Chaos in Warhammer 3, and specific flavours this time. These god-specific brands of corruption all have different effects, slowly choking the lands they spread through, and eventually they start to resemble the domain of the god corrupting them. One day you’re ruling over lovely green fields and snow-capped mountains, and the next you’ve got toxic lakes and hill-sized cysts appearing everywhere, or everything’s covered in ash and lava. It’s great if you’re filming a metal music video, but living there sucks.

(Image credit: Sega)

When you’re playing a Chaos faction, you feel like a force of nature—especially if you’re one of Nurgle’s lot, since you can spread a variety of very nasty plagues on top of Nurgle’s brand of Chaos corruption. And you’re an existential threat to the mortal factions, which is why—with the exception of Chaos-followers like the norscans and skaven—you’re in a perpetual state of war with them. There’s no rest for the wicked.

Siding with Chaos is very tempting, then, but their opponents are also a fascinating and varied bunch. With Kislev and Grand Cathay you’ve got two armies that, at the moment, are unique to Total War. Both exist in the periphery and lore of the tabletop game, and until Games Workshop finishes its upcoming Kislev army, this is the only way to get your fix.

Kislev is all about bears and ice magic. Grand Cathay has dragons and trade. I might be underselling them a little bit. I definitely should have mentioned that some of those bears are giant magic bears that tower over everything. And maybe that the aforementioned dragons are actually Grand Cathay’s leaders, who can shapeshift in the middle of battle. You’re meant to pick your moments and switch between your forms depending on the situation, but if you tell me I can shapeshift into a dragon, I’m going to shapeshift into a dragon and then stay that way. They are excellent dragons.

(Image credit: Sega)

It might not be as out-there as the Daemons of Chaos, but I’m pretty smitten with the Ogre Kingdoms. The big lads have been served up as pre-order DLC, but I expect we’ll see them sold separately later. I recommend picking them up when that happens, because these hungry boys have a lot going on, including rapidly expanding camps that can be deployed in enemy territory, the strongest economy in the game and a passion for meat that’s both a curse and a superpower.

Rags to riches

That brings us to the economy. I know, not quite as exciting as daemons fighting elemental bears. And that’s always been a problem for Total War: the economic side of things is typically an obligation rather than a system you want to engage with. Warhammer 3 doesn’t have a perfect solution to this, but it does improve things at a faction level.

While it’s easy to get rich as the Ogre Kingdoms, meat is even more important than gold. Without a constant supply of it, ogre armies turn to cannibalism. Now this technically happens in a less flavourful way with gold: when you run out, your troops start leaving. But with meat, this all happens locally. Each army has its own supply of meat, and rather than getting meat from a large pool, it gets it from the local area, either from a settlement, a camp or through battle.

(Image credit: Sega)

This pushes you to be extremely aggressive, constantly getting into fights and gobbling up new settlements to keep everyone’s belly full, but also tasks you with essentially creating a supply line to keep the troops fed. It’s not a complicated logistical challenge, but it is considerably more engaging than earning gold. And despite really just being another economic system, it reinforces who the ogres are, working in tandem with their larger-than-life personalities.

(Image credit: Creative Assembly)

On Total War: Warhammer 3’s ultra settings, I was getting between 40 and 60 fps on both the campaign map and in battle, which makes sense for my increasingly out-of-date rig.

Installed on my Crucial MX500 SSD, load times ranged from around a minute when jumping into the campaign to around 40 seconds for a battle. It’s not brisk, but it’s not torturously long. And hopefully we’ll see improvements over time, just as we did with the previous games.

Grand Cathay’s Ivory Road trading system is very different but similarly benefits from being designed with Cathay’s identity in mind. While most trading in Total War involves just chatting to other leaders and striking a deal, the Ivory Road lets Cathay dispatch caravans to distant lands, selecting the value of the cargo and the route. During the journey your caravan might be attacked or face other crises, matching the potentially huge rewards with some equally big risks. For Cathay, then, trade is an interactive adventure.

Diplomacy, like the economy, has moved closer to the heart of what Total War does, but can still feel like an ancillary feature that doesn’t get enough attention. Three Kingdom made some big leaps here, and while Warhammer 3 doesn’t include the personal diplomacy that Three Kingdoms introduced, it has borrowed the quick deal option, which makes figuring out what you can do and with whom so much easier.

(Image credit: Sega)

The headline feature, though, is brand new: outposts. When you forge an alliance with another faction, you both get the option of constructing an outpost, which adds your troops to their garrison and, more importantly, lets you recruit troops from their roster. The most obvious benefit of this is being able to fill in gaps in your own roster, but arguably its true value is the third set of recruitment slots, letting you recruit units even if you’ve maxed out your global and local allotment.

Diplomacy rewards you with incredible flexibility, which in turn encourages you to deal with your neighbours more often. Allied reinforcements cost Allegiance, which is mainly earned by completing quests for the faction you’re trying to sway, tasking you with defeating armies they have beef with, bringing the whole thing back to conflict. For a game like Total War, this is the kind of diplomacy system you want.

After hundreds of hours of Warhammer 2, the little quality of life improvements feel just as impactful, particularly the inclusion of simultaneous turns in multiplayer and simultaneous movement in both modes. You already know where your army is going, so why should you have to wait around and watch them do it before commanding the next one? You shouldn’t, and now you don’t need to bother.

(Image credit: Sega)

I’ve already sunk nearly 100 hours into Warhammer 3, which should give you an inkling of how much I’m digging it. And while I’m no longer as eager to go through the Realm of Chaos campaign again, that’s only a slice of what Warhammer 3 is. There’s a whole other domination campaign after you defeat Be’lakor, where you get to swallow up the rest of the world, helped by some special post-campaign rewards. And though I might bristle at the idea of sending my leader off to his second job at inconvenient moments before that point, it’s honestly just so much fun to play with these factions and create dream armies that I can put up with the hurdle.

While this would have been a fitting conclusion to what’s been a wildly ambitious trilogy, it’s not done yet. There will be more factions, expansions and another mega-campaign, combining the trilogy, nicknamed ‘Immortal Empires’. Total War: Warhammer 3 is already brilliant regardless of what comes next, but the prospect of six years worth of factions fighting over one map has me more excited than an ogre in an abattoir. The future looks bloody.