Elden Ring isn’t the first time a series has pivoted to open world

While previous Soulsborne games have been like 3D spiderwebs full of shortcuts and connections unlocked through careful exploration, Elden Ring is an open world of the “you can go anywhere” variety. It’s a risky shift for a studio famous for games with intricate level design.

Open worlds go way back, through the likes of Elite and every RPG with an overworld map to the earliest text adventures. But the modern idea of what an open world can be was codified by the success of Grand Theft Auto 3, which made marketing departments see dollar signs in phrases like “living, breathing world” and “you can go anywhere”.

GTA3’s reactive world, the systems that were just complex enough to encourage emergent gameplay, the collectible hunting and the strict delineation between story and side missions—all became codified into a formula that could be applied to other games and other genres.

Ubisoft are the masters of this, refining that formula by adding maps that fill with points of interest each time you reach a vantage point, outposts to liberate, and a proliferation of other repeatable activities copy-pasted in different locations. At its worst, these games become pure icon-chasing, moving from one question mark to the next where the answer to that question is usually “a sidequest that’s just like the last one.”

Yet there are still games that pull it off, that find novel ways to expand without diluting themselves. The following series all embiggened themselves partway through, and each is an example of the potential payoffs and pitfalls.

The Witcher

(Image credit: CDPR)

See these fields? All this used to be a sequence of connected hub areas.

The first two Witcher RPGs were nonlinear and had branching stories, but The Witcher 3 went fully, expansively, open world, and made a success of it. Whichever direction you go, it feels like you find sidequests as rich as the main storyline. The one with the baby in the oven, or the monster-filled manor, or the talking pig, or a dozen others.

The funny thing is, The Witcher 3’s map also contains plenty of recycled monster nests, smuggler’s caches, and other activities ripped direct from the Ubisoft template. It’s just that there are enough memorable sidequests around them to make us forget all that stuff. While Elden Ring isn’t going to have the luxury of having Geralt face a new moral quandary every 10 minutes to keep things interesting, if its side dungeons turn out a bit bland but then every one has a killer boss fight at the end, players will probably forget and forgive. – Jody Macgregor, Weekend/AU Editor

Batman: Arkham

(Image credit: Warner Bros.)Far Cry

It’s practically cliché these days among games journalists to say you preferred the original Arkham Asylum to its later open world sequels. But I think it’s undeniable that, for all the series gained from going open world, it lost a lot of its focus and sense of place.

That first game is, essentially, a metroidvania, and as with most games in that genre, the need to return to old areas and explore every nook and cranny as you gain new abilities really leads you to become intimately familiar with the space. If you’ll permit me another cliché: the Asylum is like a character itself, one you get to know just as well as Batman or the Joker.

I don’t think the same is true of Gotham in the sequel, Arkham City. To achieve open world scale, it needs a certain amount of filler—generic buildings and streets, which exist largely just to be glided over. As you travel, icons and side activities constantly fight for your attention—a far cry from the singular forward (and sometimes backward) momentum of Asylum.

Of course, with that increase in scale came a real elevation of the superhero fantasy, and for that reason many love City, and even its follow-up Arkham Knight. But for me I think no matter how well-crafted those sequels were, they turned the series into something a little less interesting.

I suspect many will feel the same about Elden Ring. The Dark Souls games are, in their way, quite similar to metroidvanias, especially in how their maps coil and twist around themselves, introducing new routes and shortcuts as you go that reveal you to be in one interconnected space, not a strictly linear series of levels. There’s a real intricacy to the design of those worlds, and it’s hard to see how Elden Ring can maintain that in its huge open areas. It may be that they make the game exciting in a whole new way—but I suspect many die hard fans will feel that something has once again been lost along the way. – Robin Valentine, Print Editor

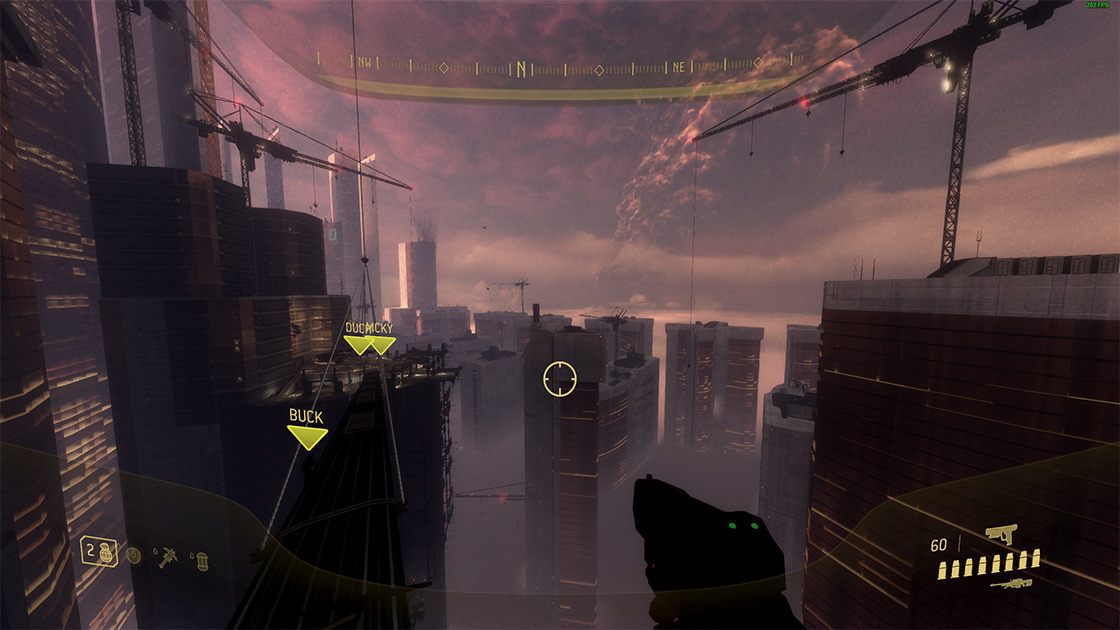

(Image credit: Ubisoft)

Far Cry was always destined to be an open world series. Even the original, which had mostly linear levels, took place on big slices of map that gave the impression of an open world. Far Cry 2 took a step closer with two huge maps, each forming an open world experience where you could go where you wanted and approach missions with freedom. Each game since has been fully open world, and that’s really become Far Cry’s identity as a shooter.

Which isn’t to say it’s been a flawless transition. Ubisoft fumbled the formula in a few of the games, overstuffing the map with icons and distractions as if it was worried players would lose interest if there weren’t constant animal attacks and collectibles in all directions. There are so many fast-travel points in recent Far Cry games that getting around the map quickly becomes just a matter of clicking an icon and waiting a few seconds. Ubisoft builds big, beautiful open worlds but then makes it so easy to traverse them that a bit of the mystery and challenge is lost. – Chris Livingston, Features Producer

Metal Gear Solid

(Image credit: Konami Digital Entertainment)

I admire Metal Gear Solid 5’s willingness to jettison the drawn-out, cutscene-heavy storytelling of the games that preceded it to focus on making an incredible stealth sandbox. We gushed about all the toys MGS5 gives you back when we awarded it game of the year in 2015, and it’s still a great example of how flexible open world design can be. Despite their size, too many open world games lead you by the hand from one mission setpiece to another. MGS5 swung hard the other way, giving you an almost ridiculous degree of freedom in how you approached infiltrating an enemy base to rescue a VIP or assassinate a target.

The open world itself is a relatively dull desert—traversing it isn’t as engaging as parkouring across rooftops, and there are no stories like The Witcher 3’s to make it come alive with a sense of place. But it doesn’t need those things when the toys it gives you are so much fun; it’s OK for the open world to simply exist as a container that holds the enemy AI you’re poking and prodding. The more elaborate a plan you concoct, the more you’ll get out of how MGS5 reacts. It’s kind of amazing the developers didn’t just come up with the Fulton launcher, the best tool in gaming history, and call it quits right there. Elden Ring seems like it may similarly be trading away some of its intricate level design, but in return it’s promising far more flexibility in how you build your character, which may well make it as malleable as Metal Gear Solid 5. – Wes Fenlon, Senior Editor

Mass Effect

(Image credit: EA)

One of the weakest parts of the first Mass Effect were its ‘unknown worlds’, the mostly blank planets scattered with warehouses for bad guy storage and not much else. If these pocket open worlds hadn’t been so boring, we wouldn’t have been annoyed by the Mako we had to drive across them. It wasn’t until Mass Effect: Andromeda that the series really embraced open world ideas, however, and we all know how that went.

Every planet had a checklist of tasks to complete, a certain amount of which had to be ticked off to make it viable for habitation, and those tasks frequently relied on backtracking—sometimes sending you to whole other planets and back again. It was like being guilt-tripped into sitting through loading screens. The lesson’s an easy one: just because there’s a lot of space on the map doesn’t mean you have to use it all at once. – Jody Macgregor

Dragon Age

(Image credit: Bioware)

Dragon Age: Inquisition continued the structure of its predecessors, having an overworld map split into lots of discrete zones you could load into. But it clearly still hoped to evoke an open world, by making each of those zones its own large sandbox full of sidequests and collectibles.

Some disgruntled fans at the time compared it to a singleplayer MMO, but in truth what it really felt like was a halfway house. You could see the developers caught between the way they were used to doing things, and some kind of greater ambition. That was further complicated by having to build the game with DICE’s in-house engine, tech that was both unfamiliar and not well-suited to a top-down RPG. A harbinger of worse to come with Mass Effect: Andromeda.

In some ways it did work—it’s certainly the most expansive vision of Thedas BioWare has created yet, and I had a lot of fun journeying across its inventive landscapes as my companions bickered. But it certainly led to a lumpy pace, and a lack of clear direction made it easy to get lost in pointless busywork without even realising it.

Case in point: the Hinterlands. The game’s first zone is enormous and bland, a sort of generic grassy starting area. Players used to the traditional structure of Dragon Age assumed they’d need to clear out all the sidequests before continuing, or else risk not getting to complete them—not realizing that Inquisition’s later structure actively encourages you to revisit earlier areas. After hours and hours of looking for lost sheep and picking herbs with no progress in the main story, many simply gave up in frustration. A worse mismatch in expectations between playerbase and game is hard to find, and ‘skip the Hinterlands’ has become a meme among the community.

I’ve no doubt the next Dragon Age will be open world too, and perhaps the fans will be more ready for it this time—but I also hope BioWare has learned some lessons in how to effectively blend their storytelling and crafted setpieces with wide open spaces. – Robin Valentine

Halo

(Image credit: Xbox Game Studios)

Long before Infinite, Bungie took a stab at an open-world Halo with jazz-noir spin-off Halo 3: ODST. But far from an icon-cluttered collectathon, the rain-soaked streets of New Mombasa act as a tone piece—an open world as pure vibes, your lone soldier wandering around Covenant patrols and scouring audio logs in between more traditionally linear Halo levels.

But Infinite is where Halo goes full open-world, and sadly, I reckon wasn’t a step worth taking. Halo levels have always had an open “feeling”, but were still heavily directed and paced treks through ultimately linear spaces. Zeta Halo loses the globe (ring?) trotting spectacle of being whisked from one mythical alien setpiece to the next, leaving us with a single biome of open-world fields filled with repetitive activities in indistinct locations.

Halo, like Dark Souls, has always sported instantly memorable level design. My biggest fear for Elden Ring is that it will trade those carefully crafted spaces for something vaster and vaguer—a fear that Halo Infinite proved is more than well-founded. – Nat Clayton, Features Producer

Thief

(Image credit: Square Enix)

Thief: Deadly Shadows, third in the series, made the City a hub to explore between missions. More than just a way to split the shopping screen into locations for players to walk between, the City became part of the story. The spooky building you can’t help but notice as you pass? That’s part of the foreshadowing the Thief games excel at, and you’ll have to visit it later in a uniquely terrifying mission. As well as setting up story, the City shifted to reflect it. Factions changed how they felt about you, previously safe streets became dangerous.

The 2014 reboot had an even bigger between-meals City, though getting to the crossing points between districts became a matter of finding the right loading-screen gap to squeeze through or window to open, making it a headache to cross. And though it reflected plot developments just like the City did in Deadly Shadows, it was hard to take seriously when a district caught fire for story reasons and then continued burning without spreading no matter how long you spent there.

Changing any part of a game that players return to can emphasize the importance of events, whether it’s your favorite shop being closed after a disaster or a wanted poster updating to reflect your latest crime. That change has to make sense no matter how long we spend there, though. Fingers crossed Elden Ring’s multiple swamps won’t catch fire as well as being full of poison. – Jody Macgregor

The Legend of Zelda

(Image credit: Nintendo)

Zelda is not a PC series, but thanks to emulation the PC is the best place to play the best Zelda game, 2017’s groundbreaking Breath of the Wild. The successes and failures of this game have been discussed to death in the last few years, and I think we’ll probably have a whole ‘nother conversation about “weapon durability: good or bad?” after Elden Ring comes out (it was good, by the way). Elden Ring will surely have some obvious parallels in how it encourages discovery without using a million minimap icons or a pulsing waypoint to tell you where to go, and I’m excited to see people dig in and compare the design of the two worlds. I wonder if Elden Ring used a triangle principle similar to Breath of the Wild?

Zelda’s developers chose to sacrifice some of the complexity of the primary dungeons to focus on delivering a world that feels alive with physics and weather and time-of-day systems that all interact with one another in fastidious detail. That was all new to Zelda; none of it was building on stuff you could do in previous games. But it still felt like Zelda, because it embellished that sense of adventure that drove the best games of the series. Elden Ring seems like it’s also giving up some of the density of its main dungeons for the sake of its open world. The question we can’t answer until we play the full thing is exactly how much it’s gaining in turn, but it’s hard to imagine it really losing that incredible sense of place the Souls games have always had. – Wes Fenlon

(Image credit: 4A Games)Metro

Metro was once a series about surviving the horrors of a post-apocalypse Russia in the shelter of Moscow’s metro system. As you can imagine in a game about literal tunnels, the first two Metro games were pretty linear. It seems obvious that an eventual third game would follow a similar pattern, but 4A Games really swung for the fences with Metro Exodus. The opening hour sees the main cast break free of the metro tunnels and set out for the Russian countryside in search of a new home.

Two of the game’s four major levels are sandboxes. Neither are as big as Fallout or The Witcher, but they’re meticulously modeled regions designed to be navigated slowly. Nothing is ever repeated twice. There are a handful of side quests and bandit camps to clear out and you can always count on finding a permanent upgrade or new attachment as a reward. 4A clearly went for quality over quantity with its open-worlds, which is rare in a genre dominated by maps with a billion icons.

Metro Exodus is a bit like Breath of the Wild in that way—exploration is the fun, and there are loads of cool mechanics to keep each moment interesting. Your main goal may just be to cross a river, but along the way you’ll probably have to measure radiation and don a gas mask, mind its filter, patch holes if damaged, scavenge for ammo scraps, scout threats with binoculars, and pump air into your pneumatic pellet gun, all the while fighting irradiated monsters. 4A clearly put a lot of effort into evolving the world of Metro into a new genre with a fresh story, and it paid off. – Morgan Park, Staff Writer

Lego

(Image credit: Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment)

Between levels in silent-movie prequel parody Lego Star Wars you hung out in the diner where Obi-Wan plays noir detective in Attack of the Clones. As the Lego series tackled other licences these free-play hubs grew, and by Lego Batman 2 you could leave the Batcave and drive around the entirety of Gotham City in an adorable Lego-block Batmobile. Lego Marvel Super Heroes had a recreation of Manhattan packed with goofy side stories—in one you have to track down a sax for Drax—and by Lego Lord of the Rings they just threw all of Middle-earth in.

What makes the Lego open worlds great is how off-kilter they are. While the main levels are usually playful recreations of familiar story beats, things get real wild in free-roam, where you can visit a zoo as Iron Man and ride around on a lion, or race pigs through Hobbiton. I don’t expect to be able to do either of those in Elden Ring, but that sense the rules of tone and what’s permissible are more relaxed away from the main story can make an open world a nice retreat from the plot, a buffet of light snacks to pick at between meals. – Jody Macgregor